|

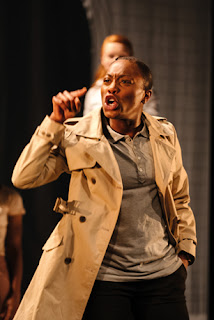

| Photo: Jack Offord |

“What mortal man is not guilty?”

An ancient Greek tragedy by Euripides, this modern re-telling of Medea is written by Chino Odimba for the Bristol Old Vic in yet another innovative and exciting production from this fabulous theatre.

In the classic Greek play, Medea is abandoned by her husband Jason (of ‘And The Argonauts’ fame) for another woman, and then threatened with exile from her homeland by his father. And to avenge Jason, she calmly kills their children in an effort to take control of her own destiny.

So buckle up, folks, this is going to be a bumpy ride.

In this new version, Odimba weaves Euripides' ancient world with a contemporary story of a single mother Maddy who faces losing her children and home following 11 years of marriage after her husband Jack takes up with another woman.

Performed by an all-female cast and using the tribal power of song while led by director George Mann, this production asserts Medea as a powerful female character who fought against the injustice of the patriarchy at all costs.

The strength of an all-female cast is undeniable; there is something very powerful about seeing a group of women working together for the same purpose. And the six cast members deftly flit between the contemporary and classic story, largely playing their character’s counterpart in each version.

Akiya Henry as Medea/Maddy is truly stunning, and demonstrates her mind-blowing versatility as an actor, while Jessica Temple who plays Medea/Maddy’s confidant Naomi is equally impressive - and her singing talent really makes you sit up and listen. Akiya has excellent comic timing - a skill you wouldn’t necessarily think was required in a play this intense and harrowing. But while singing her plea to Jason's father, she is genuinely hilarious in her tone of voice and knowing facial expressions to the audience. Bravo, Akiya, bravo.

While the story of Medea - the ultimate scorned woman - is millennia old, the story of a woman mistreated by a selfish man who wields all the power is as relevant now as it was in 431 BC. Which is utterly depressing. When the original Medea is overlooked by Jason for a newer model, she no longer has any claim to live in even the same land as him because he has all the power. When contemporary Maddy is abandoned by her husband Jack (who stops paying the mortgage on the house which is only in his name), she is evicted and made homeless with her children. These stories are as relevant today as ever they were.

| |

|

The character of Jack (Stephanie Levi-John) is very interesting. In two separate speeches he illustrates the hatred, disgust and disregard that certain men show for women, once they no longer serve a purpose. Jack’s repulsion of Maddy, and apparently women in general, is grotesque and fascinating. He is a vocal version of the hate spewed at women every day by faceless cowards online. Jack thinks women are the cause of all the misery and suffering in the world, with their only purpose being to breed children.

The lack of loyalty that the men show towards the women in their lives is staggering, considering the loyalty Medea and Maddy showed Jason and Jack. And the disregard that Jason and Jack show for the work of motherhood and homemaking is extremely unpleasant; they see Medea and Maddy as having enjoyed easy lives while their husbands have toiled and sweated. Compare this to the loyalty and compassion shown by the women in this play towards other women and it’s not hard to join up the dots and see what’s going on here.

But it is the unity of women that shines through. The support networks, the sisterhood, the strength to hold each other up while men try to knock us down. On the cusp of a general election, at a time when the government is doing its best to marginalise women and push us into a domesticated box, while the cuts continue to disproportionately ravage services that prioritise women who have been mistreated by men… Jesus! We need a play like Medea more than ever.

The privilege of men makes them blind to their monstrous behaviour. And so even though Medea herself behaves, err, somewhat irrationally, by the close of the play when we see her standing firm, halfway up a white staircase that extends and unfolds all the way into the skies of the Bristol Old Vic’s stage, it is clear which is the dominant gender.

Please go to see it.

For more information and to buy tickets, please click here.